Miranda Hill

Miranda Hill is changing Canada's literary landscape .... quite literally. As Executive Director of Project…

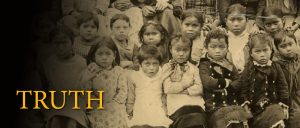

Ry Moran is Director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR) at the University of Manitoba. The NCTR is tasked with preserving, protecting and providing access to all materials, statements and documents collected by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Although it won’t officially open its doors until June 2015, Ry spent a few minutes discussing the project with Jennifer Dekker of Open Shelf.

Ry Moran

Jennifer: You’ve had a really interesting career path. How did you go from musician to indigenous language preservation expert, to Director of Statement Gathering for Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, to Executive Director of the NRC?

Ry: I grew up in Victoria BC, attended the University of Victoria and graduated with a degree in Political Science and History. Like many young people, I didn’t quite know what to do after graduation. I’d been working in fly-in fishing lodges over the summers to help pay for my university studies, so after graduation I thought I’d go up one last time to Haida Gwaii. I really connected with the Haida people and, following my heart, I decided I would stay on the islands to write my first real music album. Afterward, I realized that I needed to go back into the city to generate interest in my music – and I also needed to generate more revenue – so I started my own business.

I moved back to Victoria where I applied the technical skills I developed as a musician to preserving traditional languages. Being Métis, it was a natural fit to help first nations and Métis communities preserve and document their languages and histories. I worked with the folks at First Voices and also with my good friend Jeff Ward on creating a multi-year project to help preserve and make the Michif language more accessible. In 2008, I received a National Aboriginal Role-Model Award which brought me to Rideau Hall. I met two people at Rideau Hall who were looking for someone to get a handle on the statement gathering part of the TRC – so I offered to help.

The skills I learned in business like legal research, event planning, working with archives and digitization technology were all directly applicable to statement-gathering. It was a once in a lifetime opportunity that I felt very honoured be considered for. After conversations with the TRC for the better part of a year, I found myself interviewing for, and accepting the position of Director of Statement Gathering and the National Research Centre.

Jennifer: Ontario librarians, library workers and library board members may not yet be familiar with the NRC at the University of Manitoba. Can you explain why it is such an important part of our country’s national documentary heritage?

Ry: The NCTR is intended to be as full and complete a history of theIndian Residential Schools (IRS) and its legacy as possible. The gathering of this information into one location, whether virtual or physical, is significant because it will allow people to understand what happened and the effect that the residential school system and its legacy had and will continue to have on the country. It is vitally important to repatriate the documents into the hands of survivors and indigenous communities. Having access to the records has real meaning for survivors because many were raised for years in a residential school away from their families. Bringing these documents together allows them to reconnect with their past and their families’ past.

Jennifer: Librarians, archivists and indeed all Canadians have witnessed just how difficult it’s been to gain custody of the IRS records. How have you managed it?

Ry: We could spend all day talking about collection development because it’s very complicated. There were four major churches involved – but close to 100 different individual entities and over 20 government departments which together equalled about 120 individual archives or significant collections that held, or potentially held, residential school records. Originally, the TRC hoped to scan all of these records but the scope and size of the effort quickly outgrew the TRC’s financial capacity to do this.

The cost to produce archival quality records is incredible and is a real obstacle for some of the organizations responsible for providing their records to the TRC. To give readers an idea, at the peak of documents collection, we spent $400,000.00 – $600,000.00 a month gathering and digitizing records. Today, about 60 people work full time at Library and Archives Canada (LAC) scanning documents. Aboriginal Affairs is running the project at LAC while individual churches have hired firms to digitize. Eventually all these records will be transferred to the NCTR.

This resulted in the need for many entities to step up and scan their own documents to contribute to the NCTR collection. Some did a really good job, others did a moderate job, still others have not produced their records.

The first digitized records the government transferred to the TRC were research documents used during the litigation process and later for the Common Experience Payment process and Individual Assessment Process (historical documents only though). Unfortunately, since these records were scanned for the purposes of litigation, the quality of images is far lower than what we would hope for in a digital archival setting. On the bright side, this legal framework meant that the documents were described at the item level and have fairly extensive metadata with each record.

Jennifer: It surprised me that the centre will focus on digital records. Can you comment on that decision and speak to the opportunities for people to use the documents in their original formats?

Ry: The decision around digital records was part of the mandate of the TRC which required originals or digitized copies of originals to be transferred to the NCTR. Most organizations did not want to relinquish their originals and have produced digital copies. The NCTR has relatively few physical records – the material collection is about 2,000 unique items, mainly comprised of materials donated by the survivors and others at the TRC events as well as some records produced by churches.

During the collection and digitization of the records, where possible, the provenance of each record was captured – so that it’s possible to understand its context within the home archive. Some originating archives had better descriptive standards than others, and where the entities were supplying the records to the TRC, we had less control over the quality of the provenance information supplied. It is important to have digitized versions because it’s quite likely that the digital copy will at some point be the only surviving instance of certain records.

Having the historical record is essential: the NCTR is an institution that changes the balance of power – it challenges our common understanding of history.

Jennifer: Many Métis children attended residential schools, yet they are not part of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement. Despite this, the NRC is collecting records relating to the Métis experience and including them in the official archive. What impact has that had on the Métis community?

Ry: The Assembly of First Nations and the Inuit Kanatami were recognized in the settlement but the Métis were excluded largely because of the Métis experience of residential schools. That Métis children attended the schools is a historical fact, but more Métis attended day schools than residential schools. There were thousands of people excluded from the settlement: only 141 residential institutions were included when more than a thousand day schools operated, often with the same harmful intentions as the residential schools.

The TRC documented stories of Métis survivors. There is a chapter on the Métis experience in the short historical report and there will be a chapter in the final report. There are Métis included in the governing circle of the NCTR. It’s important for them to have a voice. There is also a separate class action lawsuit on the day schools.

Jennifer: Librarians and archivists tend to think of the information universe as being textual in nature – written documents of one sort or another. Indigenous knowledge is often not textual. Do you think there is any irony in setting up an archive to help with reconciliation for people who may not be text-based in their approach to reconciliation? How do you see the archives contributing to healing?

Ry: Aboriginal societies have always kept archives. Legal systems, archival systems, transportation systems and many other systems were well developed in indigenous societies. Part of the deprogramming of the North American mind is recognizing that indigenous societies were rich and diverse – the idea of retaining information and archiving is a traditional practice. We want to embrace the flexibility that digital records allow in order to explore ways to decolonize information structures.

Jennifer: I’m of the belief that awareness of the IRS and its documentary heritage can help me as a librarian contribute to national reconciliation and healing. With this interview, I hope to encourage other librarians and library workers to consider how they might be part of the reconciliation process. Do you have any thoughts on that? What can librarians do to move the process along?

Ry: Librarians can encourage people to seek out indigenous sources of information. Staying tuned into what is happening with the TRC, learning more about the residential school system and its impact and the resources available at the NCTR will help. Showing people the primary source documents is important. Learn to detect overt colonialism. The records we collected ask librarians and indeed all Canadians to examine their own cultural baggage…it’s important that we all think about what’s happening in this country through a lens of reconciliation and understanding the space we inhabit in new ways.

Those new ways involve understanding silences in history –the misinformation that has been taught in schools and realizing that 11,000 years of history existed on this continent before “Canada” ever came to be.

Jennifer Dekker is a Subject Specialist Librarian at the University of Ottawa serving the Faculty of Arts. She can be reached at jdekker [at] uottawa.ca.